16 One day as we were going to the place of prayer, we

met a female slave who had a spirit of divination and brought her owners a

great deal of money by fortune-telling. 17 While she followed Paul and us, she

would cry out, “These men are slaves of the Most High God, who proclaim to

you[a] the way of salvation.” 18 She kept doing this for many days. But Paul,

very much annoyed, turned and said to the spirit, “I order you in the name of

Jesus Christ to come out of her.” And it came out that very hour.

19 But when her owners saw that their hope of making

money was gone, they seized Paul and Silas and dragged them into the

marketplace before the authorities. 20 When they had brought them before the

magistrates, they said, “These men, these Jews, are disturbing our city 21 and

are advocating customs that are not lawful for us, being Romans, to adopt or

observe.” 22 The crowd joined in attacking them, and the magistrates had them

stripped of their clothing and ordered them to be beaten with rods. 23 After

they had given them a severe flogging, they threw them into prison and ordered

the jailer to keep them securely. 24 Following these instructions, he put them

in the innermost cell and fastened their feet in the stocks.

25 About midnight Paul and Silas were praying and singing

hymns to God, and the prisoners were listening to them. 26 Suddenly there was

an earthquake so violent that the foundations of the prison were shaken, and

immediately all the doors were opened and everyone’s chains were unfastened. 27

When the jailer woke up and saw the prison doors wide open, he drew his sword

and was about to kill himself, since he supposed that the prisoners had

escaped. 28 But Paul shouted in a loud voice, “Do not harm yourself, for we are

all here.” 29 The jailer[b] called for lights, and rushing in, he fell down

trembling before Paul and Silas. 30 Then he brought them outside and said,

“Sirs, what must I do to be saved?” 31 They answered, “Believe in the Lord

Jesus, and you will be saved, you and your household.” 32 They spoke the word

of the Lord[c] to him and to all who were in his house. 33 At the same hour of

the night he took them and washed their wounds; then he and his entire family

were baptized without delay. 34 He brought them up into the house and set food

before them, and he and his entire household rejoiced that he had become a

believer in God.

Tomorrow is Memorial Day. For many of us, as Christians,

this Sunday morning before Memorial Day Monday can be uncomfortable. Last year

I read a wonderful trilogy of books—Ian Toll’s history of the naval side of

World War II in the Pacific Ocean. They were long books, detailing every major

engagement with the planning, logistical, and strategic components that went

into them. They were a sobering reminder of the human cost of warfare. What our

country did to get through WWII—even just in one arena and in one branch of the

service—was staggering. Ian Toll made me proud to be a part of my country’s

history. The costs that were involved in our story have to be remembered and

celebrated. How close that contest came—and what the consequences would have

been had it turned out differently—must be passed down.

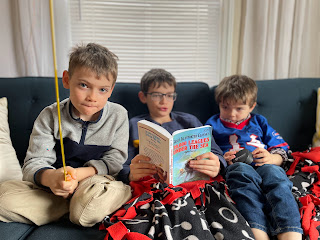

On the other hand…I was driving back across the city last

week and my boys spotted the billboard on 490 offering prayers for the victims

of the Buffalo shooting. Julie and I hadn’t talked about it with them yet. I

tried, while driving, to explain to them what had happened and what it meant. They

had questions, and they were good questions. Why did this man think it was okay

to hate black people? Why was he able to get a gun? Why can’t the president

just make guns illegal? Why can’t we change the laws so that the president can

make guns illegal? How come people on the internet are allowed to say mean

things about people with black skin? I didn’t have answers for their questions.

And I didn’t have an answer when the Texas shooting happened this week.

There is something deeply wrong—something evil--in our

country and with our way of living together that this could happen again and

again…and part of our vocation as Christians is to challenge, to name that

evil, and to try to be a part of its healing.

It's in this tension of loving our country and

celebrating its heroes, and also calling out the deep and seemingly insoluble

problems that are tied up with our culture and its structures of power, money,

and justice, that a slave girl has a lesson for us. She’s called a paidiske.

That can be an affectionate name for a child, or a term for an enslaved person,

or a leering term for a prostitute. Whatever her actual name was, and wherever

she came from, our story is going to start with her, and as you’ll see, there

was something special about her. She had a gift.

First, a word about worldview and context. As a warning,

this is going to be a long walk for a short lesson, but the context about

slavery and superstition in 1st century Rome is essential to getting

into why the characters in our story act the way that they do. We are going to

put ourselves in the sandals of the first century AD, and part of that world,

as inconceivable as it is to us that this could ever be normal for any

compassionate person…is slavery. To understand the anger of the Philippian men

at Paul and Silas, remember that they grew up in a world with slaves, had never

heard of a world without slaves, and probably had no conception of a world

which wouldn’t have them. Like any piece of property, slaves had their prices—probably

about 1,000 denarii for a “used” slave, with as little as 500 denarii for a

slave in poor condition to as much as 6,000 denarii for an “unspoiled” female

slave. That context is especially important later on. Using some very back of

the envelope math, that converts to something like 5,000 modern dollars for the

lowest end to 60,000 for a highly desirable woman. Or, in other words, the

market for slaves was roughly analogous to our market for cars. And yes, we all

should feel revolt at putting a number on a human being in the same way that we

price an automobile. The only defense of that system is that anything else was

unthinkable—just as it is unthinkable to us except as a passing fancy that our

descendants might someday judge us for putting similar prices on

pollutant-emitting internal combustion engine driven vehicles.

The second element of the Roman worldview that will help

make sense of our own relationship, as Christians, to the secular state that we

live in and love, is Roman superstition. If you went up to Brittania, which was

a Roman colony by this point, you would hear stories of fairies in the woods.

Most of the druids had been driven out of France by this point, but the

assumption was that in these wild places—the colonies, the forests of Germany—there

were ghosts and spirits. In the fens of Denmark people whispered stories that

eventually were handed down and became the story of Beowulf. There were spirits

in the trees, dark gods that lingered in the caves of the mountains—and even

aside from the outright “magical” superstitions, there were mountain lions,

wolves, wild boar, and creeping snakes.

It was a dangerous, uncertain, risky world to live in.

And one of the ways that people held together and kept their sanity in this

world—a world where gods were everywhere and not necessarily friendly to human

affairs—was to engage constantly in what we would regard as superstitious

nonsense.

This looks ridiculous through the lenses of our

worldview, late Western modernity. Think about checking the weather. A

lightning strike for us just means pulling our phones out. The storm is

expected to last until 8 PM—easy, scientific knowledge. This way of ours of

separating meaning in the natural world from our own lives would have been as

unthinkable in the first century as their way of detaching humanity from slaves

is to us.

The interpretation of superstitious beliefs, events, and

(critically), the payment for those services in Ancient Rome was licensed and

controlled by the Roman state, and it was done by professional seers.

Professional seers, whatever their rank and station, were

not trying to read the future. Even though we use the word ‘fortune

tellers’ in many translations, they were trying to figure out what the will of

the gods was for a given course of action, or given a new event. Julius Caesar

is on campaign in Gaul Should we attack on enemy tomorrow? Caesar would

regularly put off battles because his augurs would make sacrifices and get

unfavorable readings. That was enough to keep the army in camp for another day.

Whether or not (and, in our scientific, late Western mindset, we know not)

these readings actually showed the will of the gods for Caesar’s battle plan,

the reading of the sacrifices was an important part, a public part—even the

center of the corporate life of the camp. So even if Caesar wanted to press

ahead, though he’d received an unfavorable omen, he couldn’t—because all of the

soldiers under his command would know that something was wrong about the liver

of the pigeon. This was an essential part of who this community was, not a

private and individual action like looking up your horoscope or getting scratch

off lottery-tickets with your phone number, but a public good, like a weather

report, or an amber alert, or a road closure sign. It was called “taking

auspices.” There were five ways that someone could take auspices:

1 Ex caelo. From heaven. This was watching the sky,

usually trying to interpret lightning strikes and unusual weather events. The

senate, for example, was not allowed to meet during lightning storms, and there

were also bits of knowledge actually approaching meteorological science rather

than bald superstition that were passed down through this method.

2 Ex avibus. From birds. Oscine birds gave augury by

singing, and alites by flight. Eagles, vultures, ravens, and owls were birds of

particular importance, and it was interpreting the meaning of unusual bird

appearances or bird behavior that the lowly haruspices had their best chance at

earning employment.

3 Ex tripudiis. By dances. This is my favorite type of

augury, because it involves the sacred chickens. In this practice the will of

the gods was determined by feeding the sacred chickens and watching them to see

if they ate greedily or not. The emperor Tiberius once (to the scandal of all

who were present) threw the sacred chickens overboard after they refused to eat

while waiting for a favorable auspice on his home in Capri. The tripudium was

especially important on military expeditions, and probably (this isn’t too much

of a stretch to imagine) because chickens always eat greedily. One of the games

that my brothers and I would play growing up—we always had a couple dozen

chickens—was to throw a single cherry tomato into the coop and provide color

commentary to the cherry tomato football game that followed. Chickens ALWAYS

eat greedily.

4 Ex quadripedibus. By four-footed animals This method

was unsanctioned for official state augury, but regarded as even more reliable

because it was unofficial. Crossing paths with an animal in ancient times meant

something, and the bigger and/or snakier, and/or more unusual the animal, the

more important the auspice was. Our superstition of black cats crossing our

paths is a fossil of this practice.

5 Ex diris or ex signis. By signs or marvels. Sneezing,

stumbling, flames, funny noises. St. Elmo’s fire. Anything not readily

classified above.

We are most concerned next with WHO could take these

auspices, and we start with the lowest and most unreliable class of auspice

takers—the haruspex, or the haruspices in the plural. Again, their job was

discerning the will of the gods, not predicting what was actually going to

happen. Haruspices had a professional union, but no official status with the Roman

state. They were like mall security—reassuring to know that they were there,

but if there was a problem you would definitely assume that the real police

were going to be called right away, and that the guy in the mall security

office was going to hand the situation over as soon as possible. As easy as it

is to make fun of them, Roman society couldn’t function without haruspices,

because you needed to take auspices for practically everything—from naming

babies to taking boat trips to throwing parties—and to do it without a cheap,

everyday option would be prohibitively expensive.

Official Roman state augurs, however, were trained,

sanctioned, and better-trusted. Though not particularly well-paid or of exalted

standing in Roman society, augurs were necessary for every public transaction. The

historian Livy says that “by auspices this city was founded, with war and peace

led by auspices, all military and private affairs conducted by auspices…”

Critically here, there is a tension in the balance of power, because the professional

augurs were needed to validate auspices, but they were actually taken by

magistrates—that’s a military term, and the same word that we heard in the

passage—and it was the magistrates themselves who were needed to the actual

spectio (or watching) and nuntiatio (interpretation.) Our word “inauguration,”

literally means the bringing in of an augur—you would never swear in a public

official or start an academic term or a sporting event without first taking

auspices.

So we have haruspices trying to read these signs, and

then we have a whole college of augurs reading these signs. At this point I’m

summarizing Cicero’s summary of the “science” of augury from On Divination, and

here’s what he says next:

"Speaking now of natural divination, everybody knows

the oracular responses which the Pythian Apollo gave to Croesus, to the

Athenians, Spartans, Tegeans, Argives, and Corinthians. Chrysippus has

collected a vast number of these responses, attested in every instance by

abundant proof. But I pass them by as you know them well. I will urge only this

much, however, in defense: the oracle at Delphi never would have been so much

frequented, so famous, and so crowded with offerings from peoples and kings of

every land, if all ages had not tested the truth of its prophecies.”

Cicero is describing the most famous and most prestigious

form of divination in the ancient world—the Oracle at Delphi, the incarnate

spirits of Apollo called the Pythians.

He’s actually defending the Pythians against the charge

that they may have declined slightly in recent times, but it is clear that even

in a slump the Pythia remains the “Harvard” of professional seers. There’s the

Pythians, and then there’s everyone else that competes for 2nd place.

There were a number of “pythian” women at any time living

at Delphi. They were famous for giving their answers in verse, and for crafting

them very cleverly in terms that could be interpreted several different ways.

(Even though this wasn’t helpful for discerning the will of the gods, this was

generally regarded as being inspired and impressive.) A pythia was bold and did

actually predict the future. A pythia was trusted because she regularly got

those predictions right. A pythia was frightening because she foamed at the

mouth and looked possessed as she spoke. Coming face to face with the spirit of

the pythia (generally regarded as the god Apollo speaking through someone’s

voice) was an unsettling experience, but as valuable as a whispered stock

market tip from Warren Buffett.

The slave girl in this passage, having the spirit of

divination? Echoun pneuma puthona. She was a pythia. We talked earlier about

the economic realities of slavery in the ancient world, and how slaves were

similar in value to cars in the modern world. When Paul cast out the pythia

spirit, he didn’t just wreck somebody’s car. This was like losing ownership of

an NFL franchise. A pythia was the GOLD standard of augury in a world that required

augury for everything. Their “hope of making money” wasn’t reading horoscopes

for pennies—it was of making a life-changing fortune. Paul publicly made the

pythia spirit go away—it was an unthinkable amount lost, for both her owners,

and (keep in mind, the magistrates are needed to interpret the prophecies) the

magistrates.

Now, note what happens when real money gets involved,

because this is where we suddenly pivot back to something recognizable in the

modern world. Those that stand to lose big strike back immediately, by stirring

up resentment against Paul and Silas because they are of a different religion.

A different race. A culture not our own—traditions we Romans are not allowed to

practice. They circle the wagons of their own religious and political

traditions and use fear-mongering to play on the worst instincts of the crowd.

The owners of the slave-girl have Paul and Silas thrown in jail by the

magistrates (who, keep in mind, are needed to interpret and announce any augury

that happens in Philippi) and they are locked away.

And here is the lesson for us--they don’t resist, and

when the doors to the jail burst open, they don’t walk out. When we challenge

something that big, we stand in the abuse of our oppressors and we don’t resort

to our own legal rights, but we take their hatred until they have spent their

hate and we have saved them. This passage ends with the jailer bathing Paul and

Silas in his home, in the waters of hospitality, and Paul and Silas bathe his

household in the waters of baptism. This is a new kind of living, one that has

never been seen in the world of the 1st century. It is a way of

living that needs to be seen in the 21st century—Paul and Silas did

not take a legal case to the Supreme Court to insist on their religious rights,

and they did not publicly defy the authorities or form a political action

committee. Now, Paul is shrewd, and he does do something like this at other

times—even challenging the Philippian magistrates in the next chapter. But when

it comes down to his own rights in setting things right for this slave girl, he

is not a baker arguing for his religious rights to avoid making cakes for gay

couples—he goes to prison, and loves his jailer until they are washing each

other in the waters of forgiveness and healing.

This has always been a part of the Christian vocation,

and as much as we’ve struggled in this country and in this time to find a

nuanced and appropriate way of being proud children of our country and also

honest critics of our country, there are examples that show us how to be

citizens of Jesus’ Kingdom. In fact, there are modern Christians who have

challenged institutions as massive, as unthinkably embedded, and as profitable

as the office of the Delphic Pythia.

In 2012 Megan Rice, a Catholic nun, entered the Y-12

National Security Complex in Oak Ridge Tennesee illegally to advocate for

nuclear disarmament along with two fellow activists. She went to prison for

this. She was 82 years old. She went to federal prison. It wasn’t her first time. She also served two

six month prison sentences for protesting at the US Army School of the Americas

in Fort Benning Georgia, where she was arrested for demonstrating against the

US Military torture instruction which had taken place there.

In 1917, a 20 year old woman was arrested for picketing

the White House on behalf of women’s suffrage. She went to jail, and would be

imprisoned four more times for protesting against nuclear proliferation. Her

name was Dorothy Day.

But perhaps the best known story, my favorite, and the

one that we’re going to sing about momentarily, is the story of John Newton.

The captain of a slave ship, Newton became a Christian aboard the HMS Greyhound

in a severe storm. He read the Bible and decided to swear off profanity,

gambling, and drinking. No one minded that. He also decided to devote the rest

of his life to bringing down an institution that was massively profitable, and

without which the world seemed unable to function properly. He became an abolitionist

and took on the slave trade. He never went to prison. But he did both love his

country and challenge his country’s deepest flaws.

May God give us the amazing grace to suffer on behalf of

the slave girls, and on behalf of our country, until its deepest, most

embedded, and unthinkably cruel faults have been cast out in the name of Jesus’

kingship, and we are being washed by and washing those who fought us the

hardest. Alleluia, Amen.